Milk is a limited series art journal featuring written and visual art works by artist-mothers about motherhood. There are a total of three volumes in the series, each organized according to a theme and with a selection of work from contemporary artists worldwide. Edited by Katherine Oktober Matthews, Milk art journal includes artworks of diverse media including photography, painting, collage, fiber-based art, sculpture, and pottery, writing in the form of poetry and articles, and interviews with artists and authors. The journal is available as an ebook and printed journal (available by print-on-demand) from publisher House of Oktober.

To get in touch, please email: hello@milkjournal.art

More about the project

The purpose behind Milk is first and foremost to create an art journal of beautiful and important works, but beyond that, it’s to give space and serious consideration to works by artist-mothers about motherhood. The “artist-mother” figure is still sidelined in today’s art world, and furthermore the topic of motherhood is often overlooked as a serious art subject when it comes from the mothers themselves (i.e. it is far more common and widely accepted to portray motherhood from the outside, as in taking a mother as a muse or describing motherhood as a metaphor or an archetype). The intention with this project is to collect artworks by artist-mothers about motherhood which are high quality at an international level, to generate more credibility and add to the canon.

Artists are historically and contemporarily rewarded for being rebellious, countercultural figures – this quality goes virtually hand-in-hand with what “creativity” implies, which is something apart from the norm. This creates an implicit bias against traditional roles such as motherhood. As asked by author and art critic Hettie Judah in her recent book How Not to Exclude Artist Mothers (and Other Parents)[1]: “For what is one to rebel against if not domesticity and the conventions of family life?”

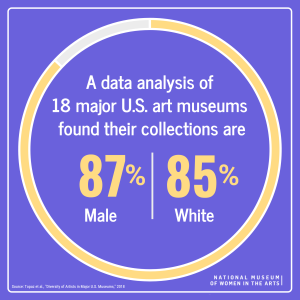

This compounds an already unequally gendered art world: In the Netherlands, where House of Oktober is based, only 13% of the art in Dutch museums is made by women[2]. In the U.S., the National Museum of Women in the Arts reports that 87% of the works in major museum collections are by men and only 8% of galleries represent more women than men.[3][4] The UK doesn’t fare better: In 2022, The Times reported that just 25 pieces in the National Gallery’s collection of 2391 artworks were by women, a touch more than 1%.[5]

This compounds an already unequally gendered art world: In the Netherlands, where House of Oktober is based, only 13% of the art in Dutch museums is made by women[2]. In the U.S., the National Museum of Women in the Arts reports that 87% of the works in major museum collections are by men and only 8% of galleries represent more women than men.[3][4] The UK doesn’t fare better: In 2022, The Times reported that just 25 pieces in the National Gallery’s collection of 2391 artworks were by women, a touch more than 1%.[5]

Most of us know the Tracey Emin quote: “There are good artists that have children. They are called men.”[6] Or take Marina Abramović: “In my opinion [having children is] the reason women aren’t as successful as men in the art world.”[7] Motherhood presents many challenges to the production required of artwork, including dedicated time for producing work, a workspace apart from children to keep them away from hazardous materials or expensive equipment, a precarious financial situation for work that is often speculative or freelance, and institutional biases that expect artists to travel, network, and be available during times incompatible with caregiving. All of this is in addition to the vague – but incredibly real – problem of the art world responding to the “aura” and image of an artist, which tends to look down upon mothers as uninteresting, artistically speaking. As put by Marilyn Minter: “The art world loves young bad boys and old ladies.”[8] This means, too, that artist-mothers are passed up by galleries for representation, which is one of the gateways to museum acquisitions, and grant and residency awards—all of which contribute to the market value of an artwork and the prices that an artist can demand for her work. The results of this are self-perpetuating: because artist-mothers are systematically excluded, younger artists continue to learn that you cannot be both an artist and a mother. As put by young Dutch artist Femmy Otten just this summer: “At the academy, the message was that you had to choose. You either become a mother or an artist.”[9]

Beyond the problems of production and dissemination, there is also bias against women taking on the subject matter of motherhood. While some artists have been recognized for their work about family and the domestic, this is both exceptional and circumstantial: Few female artists have risen to international stature this way, and this is also a result of women being excluded from having access to the full range of topics afforded to men. Catherine McCormack writes that, “there was such anxiety over the thought of a group of women scrutinizing and understanding a nude male body that women were almost entirely kept out of professional artistic training until at least the end of the nineteenth century, and even up to the middle of the twentieth century in the UK.”[10] Motherhood as a topic is valorized primarily when seen through the male gaze, when a woman is looked upon as a muse, as an idealized symbol or myth. This “othering” of the subject enables an abstraction layer that allows male artists to claim they’re making universal statements about motherhood. Yet, as put by curator Helen Molesworth: “[M]ost men think that men make universal statements and women talk about women.”[11] The outcome is damaging not only to art but to our understanding of what motherhood actually is. Because “the vast majority of Western art history’s early representations of mothers were heavily influenced by the male perspective,” writes Salomé Gómez-Upegui, “images of motherhood were often one-sided, reflecting expectations rather than realities.”[12] The reality of motherhood, as represented by mothers, remains elusive in the art world. “Invisible social structures have, for generations, failed women, their children and their art,” argues Francesca Wade. “We are all the poorer for it.”[13]

[1] Judah, Hettie. How Not to Exclude Artist Mothers (and Other Parents). Lund Humphries, 2022.

[2] Research by Mama Cash, cited by Stedelijk Museum Schiedam for their exhibition “Masterly Women”, 2019.

[3] National Museum of Women in the Arts, online. “Advocacy page,” accessed September 2023.

[4] Chalabi, Mona. “Museum Art Collections Are Very Male and Very White.” The Guardian. 21 May 2019.

[5] Kelly, Liam. “Works by women make up just 7% of art in top galleries” The Times. 10 April 2022.

[6] Alexander, Ella. “Tracey Emin: ‘There are good artists that have children. They are called men’,” Independent. 3 October 2014.

[7] Puglise, Nicole. “Marina Abramović says having children would have been ‘a disaster for my work’,” The Guardian. 26 July 2016.

[8] Rigg, Natalie. “Marilyn Minter Proves She Can Still Provoke and Perplex,” SLEEK Magazine, 6 December 2016.

[9] Bruinen, Marsha. “Natúúrlijk is het kunstenaarschap met kinderen te combineren – in theorie, althans” (Of course you can combine being an artist with children – at least in theory”), de Volkskrant. 22 May 2023.

[10] McCormack, Catherine. Women in the Picture: Women, Art and the Power of Looking. Icon Books, 2021.

[11] Halperin, Julia. “Creating value around women artists: the chief curator’s view.” The Art Newspaper. 4 May 2016

[12]Gómez-Upegui. “How Women Artists Are Shaping the Way We See Motherhood.” Artsy. 5 May 2021.

[13] Wade, Francesca. “Six Artists Balance Creativity and Motherhood. Results Vary.” The New York Times. 26 April 2022.